USS Pandemonium at Treasure Island; photo courtesy US Navy All Hands magazine, July 1957

In the summer of 1946 the United States exploded two atomic bombs in the Bikini Atoll of the Marshall Islands—a small ring of islands 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii—as part of a research project called Operation Crossroads. The event marked the beginning of the United States’ postwar regime of nuclear weapons tests, which ended only in 1992 and involved more than 1,000 nuclear weapons. Most weapons tests took place at the Nevada Test Site, northeast of Las Vegas. However, during the 1940s and 1950s, the US military exploded 67 nuclear weapons on the Bikini and Enewetak atolls of the Marshall Islands, which it had renamed its Pacific Proving Grounds: an outdoor laboratory where the military “tested” theoretical advances in its weapons technology. To produce the Pacific Proving Grounds as an empty landscape available for weapons testing, the United States first removed indigenous Bikinians, promising to return the island after the tests were done. Bikini remains uninhabited today.

Nuclear weapons testing bound the Marshall Islands with another island in the middle of the San Francisco Bay. Treasure Island is a manmade landmass, constructed between 1936 and 1937 for the Golden Gate International Exposition and taken over by the US Navy in 1940, on the eve of the United States’ entry into World War II. It is connected to a natural island, Yerba Buena, which had served as a US military outpost since 1867. Naval Station Treasure Island was a receiving station for navy sailors coming to and from the military’s operations in the Pacific Ocean. It also housed several training schools, like the island’s damage control school. With Operation Crossroads, the United States committed to its postwar nuclear weapons program, and Treasure Island’s damage control school began offering new courses in “ABC warfare,” or atomic, biological, and chemical defense.

The US military’s weapons tests were simultaneously experiments for the military and real disasters for the Marshall Islanders (and the entire planet). Similarly, at the same time that students in Naval Station Treasure Island’s damage control school learned methods of radiological protection, they practiced for nuclear war using real sources of radiation. For example, in the 1960s, the damage control school’s course in atomic, biological, and chemical defense included exercises on the USS Pandemonium, a 173-foot mock patrol boat built from salvage and scrap parts, and stationed on the northwest corner of Treasure Island (it was later moved to the northeast corner). Wire cables ran through the Pandemonium, connected lead-shielded boxes containing radioactive cesium-137 to a control room on board. A water tank on the ship held a diluted solution of radioactive bromine-82. During “practice” exercises, the cesium and bromine were used to simulate nuclear fallout, while navy students wandered the practice ship’s decks in rubber suits, learning to use Geiger counters. Yet this practice radiation ultimately became a problem of public health: in the spring of 2013 two independent laboratory analyses funded by the Center for Investigative Reporting found high levels of cesium-137 on the then-shuttered military base, near civilian homes. Today, as the navy attempts to remediate (the technical term for “environmental cleanup”) Treasure Island, it confronts radioactive waste produced through its former training exercises.

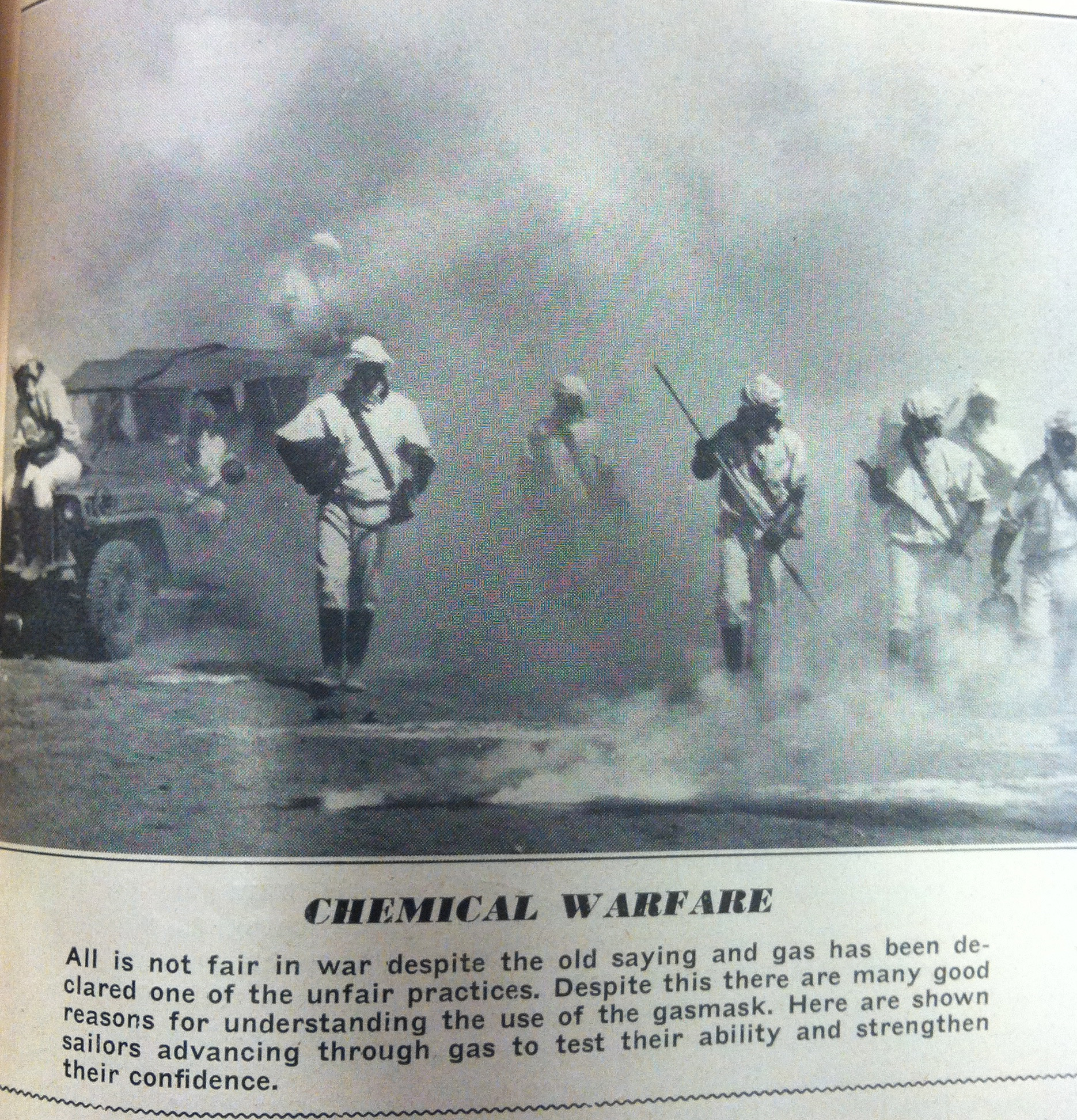

Naval Station Treasure Island students practiced for chemical warfare; image from the Masthead, the local newspaper for Naval Station Treasure Island, April 9, 1948, courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, San Bruno

Treasure Island was bound to the Marshall Islands in other ways, as well: at the damage control school, navy students also trained as radiological safety monitors. These monitors were needed at military bases around the country, as well as at the Pacific Proving Grounds and the Nevada Test Site, as required staff for ongoing nuclear weapons tests.

In 1954 the US military detonated a thermonuclear bomb (the “Bravo” test) on Bikini, producing radioactive fallout that rained down on Marshall Islanders on Rongerik and Utirik atolls and initiating a public outcry that culminated in a ban on atmospheric weapons tests. (After the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963, the United States and other signatories tested nuclear weapons underground). After Bravo, the military also initiated Project 4.1, or the Bravo Medical Program, which provided medical care to exposed Marshall Islanders and secretly enrolled them in a long-term health study on the biological effects of radiation, conducted in part by the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL) at the Hunters Point shipyard. NRDL scientists, with Treasure Island monitors, had served in the military’s Radiological Safety Section for its nuclear weapons tests. However, the radiation exposure suffered by Marshall Islanders raises questions about who was protected and who was made more vulnerable through these exercises in “national security.”

In 1993 the Department of Defense (DoD) closed Naval Station Treasure Island, and today the Lennar Corporation seeks to transform the toxic military base into an eco-topic landscape of high-rise condominium towers, offices, and parks. Since the early 1990s the DoD has closed hundreds of military bases, part of a strategic, geopolitical realignment in the aftermath of the Cold War. Military bases are highly contaminated places, and the military’s waste (which, at Treasure Island, includes lead, dioxins, PAHs, PCBs, petroleum, and radioactive waste) constitutes another form of fallout. Although Naval Station Treasure Island is officially closed, it will continue to exist in soil and groundwater far into the future. In this sense, the afterlives of nuclear weapons—and militarization more broadly—represent a form of what literary scholar Rob Nixon calls “slow violence,” “a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.” Slow violence poses challenges to our cultural imaginations, in how to recognize environmental harm that occurs at speeds and scales that are difficult to recognize—at the cellular level, or over the course of generations. The challenge is posed by the redevelopment and makeover of Treasure Island today.

Lindsey Dillon is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. This post is adapted from “Pandemonium on the Bay: Naval Station Treasure Island and the Toxic Legacies of Atomic Defense,” in Urban Reinventions: San Francisco’s Treasure Island.