Community members building public garden in Chicago as part of Archi-treasures project

How do you approach the design of a space or process intended for a specific community? Shalini Agrawal has many ideas. The former director of the Center for Art and Public Life (CAPL) at the California College of the Arts (CCA) teaches CCA students to bring communities into their practices; she is founder of Public Design for Equity and co-director of Pathways to Equity, equity-driven practices for equity-driven outcomes. Joining her in conversation for Public Knowledge in December 2017 was artist and Center for Art and Public Life artist-in-residence Chris Treggiari. The two discussed what led them to community-based practice, how they had collaborated, and what skills they believed were necessary for this kind of work.

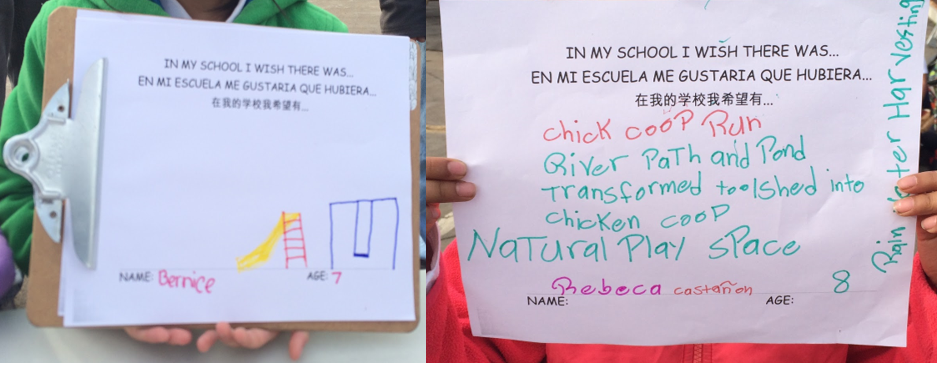

Formally trained as an architect, Agrawal worked for architecture firms in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. A trip to India transformed her thinking about design and communities, and she started to incorporate facilitating communities into her practice. As a co-founder of the nonprofit Archi-treasures in Chicago, she worked with teachers, gardeners, artists, and interdisciplinary practitioners to transform school yards and community spaces through participatory design (now known as design thinking). On the West Coast, she continued this work with the San Francisco Unified School District to engage with students, neighbors, teachers, and staff on the design of their school yards. Agrawal’s work with communities extends to her teaching at CCA, where she works with students to address needs impacting community partners through creative practices. Agrawal described the ways in which working with communities can pose unforeseen challenges, such as when residents of one West Oakland neighborhood viewed a planned community garden as a visual trigger for gentrification. With her facilitation and community buy-in, this community ultimately was able to build a garden that served as a safe space for the neighborhood.

Students describe their ideas for transforming school space in West Oakland

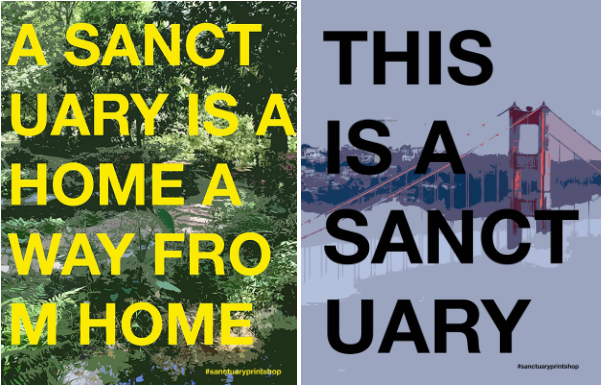

Research and collaboration are also key components of Treggiari’s projects and process. He collaborated with artist Sergio De La Torre on the Sanctuary Print Shop at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, which was part of a ten-year project on the sanctuary ordinance. Sanctuary Print Shop invited participants to create posters and engage in conversations on deportation, sanctuary-city policy, and personal safety in light of President Donald Trump’s immigration policies, including the repeal of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and increased Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids threatening immigrant communities. Through the act of printing posters, the artists were able to open up conversation and ask probing questions, such as “do you know anyone who’s been deported?” and “what is a sanctuary?” These answers were turned into posters that participants were encouraged to post in their neighborhoods.

Posters made at the Sanctuary Print Shop at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

For another project, Eyes of Oakland, Treggiari partnered with the Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR) to look at how surveillance technologies, such as domain awareness centers, impact our neighborhoods and communities. Through his Mobile Arts Platform (MAP), which features a 1965 Ford Falcon news van with a printmaking station, Treggiari went to Oakland neighborhoods and aimed to promote dialogue about surveillance through quizzes and conversation. Participants’ answers to his questions became the starting point for CIR articles and culminated in the creation of a domain awareness center at the Oakland Museum of California.

In their first collaboration—the exhibition Social in Practice at YBCA—Agrawal and Treggiari brought their respective skills and backgrounds together to explore the common language around community-based design and social practice. They asked designers, artists, and practitioners how they work with communities, how they start projects, why they do this work, and what the value of this work is. These questions then became quotations that were displayed in the gallery space and could be taken home by visitors. The exhibition became a catalyst for creating a shared set of values and components of the process for designing with communities.

Interactive community space in the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

As director of CAPL, Agrawal worked with faculty and students to partner with nonprofit institutions such as Creativity Explored, Larkin Street Youth, and the Bayview–Hunters Point after-school program. These partnerships offered students and faculty the opportunity to work on real-world projects with the potential for longevity and impact, and they extended the student community to partner organizations’ communities. Most recently, Agrawal and Treggiari, co-taught a class of students from both architecture and interior design. While many would go on to create designs for specific communities, architecture students rarely had the opportunity to meet constituents outside of their school setting and were unfamiliar with how to start conversations. The initial weeks of the class were spent learning about how to be a good communicator, activating open engagement, and navigating power dynamics. Workshops on active listening, engaged research, co-creation, reflection, and responsive iteration provided students with the tools to start working with the community.

Youth in San Francisco creating mural for community center

Treggiari and Agrawal’s combined practices and knowledge, as well as support from the numerous partnerships through CAPL, further provided students with opportunities to interact with the surrounding community. The Mission Neighborhood Resource Center (MNRC) works with the homeless population along 16th Street in the Mission district of San Francisco, providing counseling, medical services, housing support, and community programs. The Mission, once a working-class Latino neighborhood, exemplifies gentrification in San Francisco. Several weeks into class, students were eager to start designing, and they were ready to speak to their clients at the MNRC. Through conversations with and careful observations of MNRC staff and patrons, the students were able to propose creative solutions. For example, the front desk at the MNRC was in need of an update: it was too short and patrons could easily reach over the desk, which made staff uncomfortable. A student created a desk that was accessible but also created a safety barrier. Another student tested a mobile charging station for patrons that allowed for “lock and leave” and “stay and play” modes; it was still being used six months later. Agrawal’s goal was for students to learn to think about how design can address social needs, and to more deeply consider the complex role that designers can play when working with communities. This class was awarded the 2018 Interior Design Education Council’s national Community Service Award.