In the spring of 2018 I became the first artist-in-residence at the San Francisco Planning Department. I was given a badge, a cubicle-like space, and a computer with selective access to the server. For a while I felt a bit like the Finnish performance artist Pilvi Takala in her piece The Trainee, where she got a job at Deloitte and proceeded to sit at an empty desk doing nothing. (When people would ask what she was doing, she would reply that she was doing “thought work.”) I wandered around absorbing the office textures: the carpeted hush, the desk tchotchkes, the giant rolled-up plans, the amazing conflict-resolution diagram in the break room. Occasionally I would do strange things like take all of the text out of giant organizational charts I found on the server, just to see what it looked like. I made an org chart for my own “department,” with only one employee in it (me) and tacked it to my cubicle wall.

I was befriended by the people in the Office of Short Term Rentals, who happened to sit nearby. One day, one of them told me about a couple of rooms down the hall that contained a disorganized no-man’s-land of archives, including aerial images of San Francisco from the 1930s. The rooms had been somewhat repurposed; one was technically the nap room, so that you had to move a big and very comfortable recliner in order to open the flat files. The other room contained a copy machine and a giant recycling bin, which became something of a desk for me in the weeks to come.

I was befriended by the people in the Office of Short Term Rentals, who happened to sit nearby. One day, one of them told me about a couple of rooms down the hall that contained a disorganized no-man’s-land of archives, including aerial images of San Francisco from the 1930s. The rooms had been somewhat repurposed; one was technically the nap room, so that you had to move a big and very comfortable recliner in order to open the flat files. The other room contained a copy machine and a giant recycling bin, which became something of a desk for me in the weeks to come.

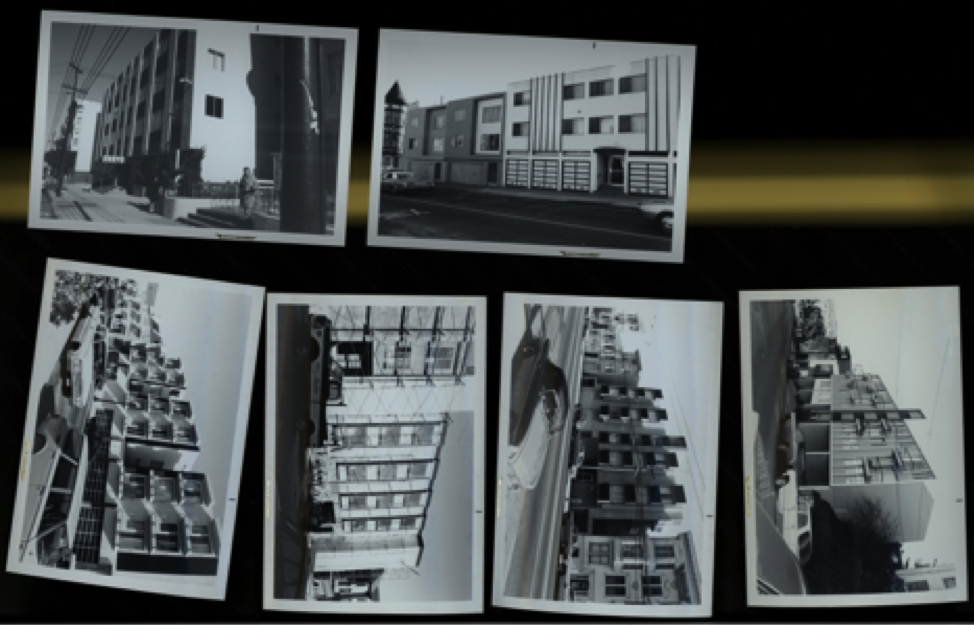

The flat files contained many odds and ends from analogue days: not only maps but slides, posters, bits of presentations, and blank certificates of historical significance never awarded. These were all very interesting, but I developed an obsession with something else: stacks and stacks of photographs that were compressed into a single small drawer in the recycling bin room. Many of them were still in their envelopes from the drugstore, dusty enough to suggest that no one had looked at them in a while. The first envelope I opened was of photos of North Beach and Chinatown in 1998 (an overwhelming number of the photos were from 1998, it turned out). I found older photos, as well: some from the 1980s with the date stamped in blue ink and smudged, and smaller ones from the 1960s with the shiny gold “Technicolor” label in the margin.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

For the most part, the photos had no context and no notes, and when I asked around, people seemed to have only a vague idea of why they were taken. But it wasn’t too hard to make a ballpark guess. In many of the older envelopes, someone seemed to be trying to document an architectural style or something that was under construction. The subjects of the 1998 photos, on the other hand, were not buildings but the life of the city: people shopping at local stores, sitting outside cafes, stopping to talk on the sidewalk. These images looked like they could have illustrated Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities; indeed, a few Planning employees suggested these might have been taken for a series of neighborhood studies done in the late 1990s.

As an artist who often works with archives, I’ve always thought that although a picture is worth a thousand words, it often only intends a single sentence. In these photos that were meant for a very specific purpose—for example, to document the use of a neighborhood for a study—there slumbered latent meanings, visible perhaps only to someone accidentally finding them in a drawer twenty years later. My readings of the photos were inevitably influenced by my being not only an artist but an outsider to the Planning Department, a former resident of San Francisco, and a person who grew up in the 1990s.

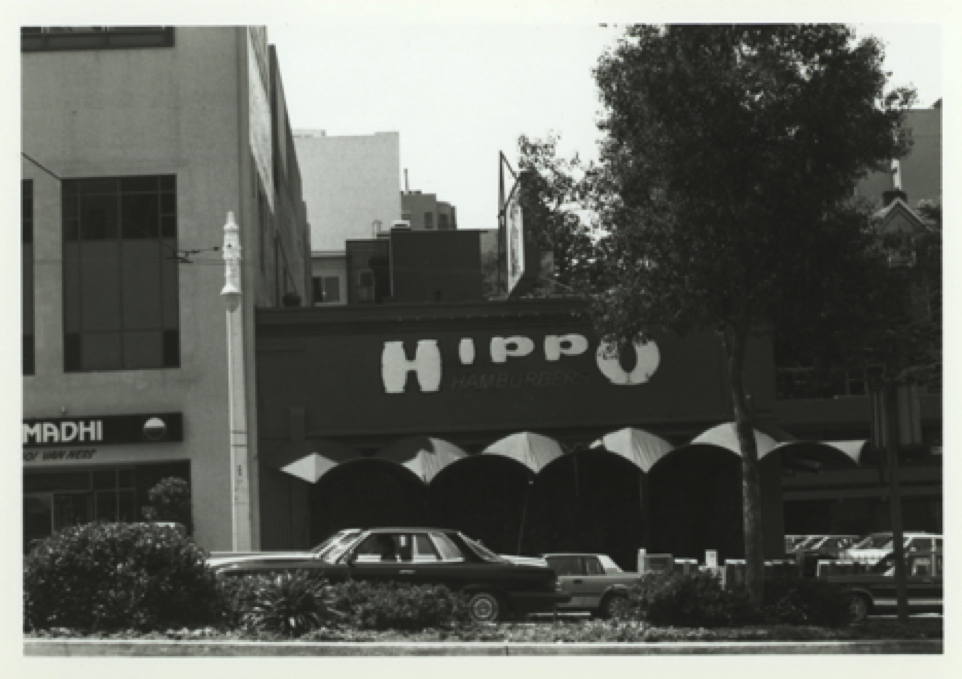

At the first and most obvious level, the photos took on an inadvertent kind of historical value—as is the case with any document that has aged at all. Encountering relatively candid images of a city I knew from a time before I knew it gave me some of the feeling that the audience has at Rick Prelinger’s “Lost Landscapes.” At this annual event, Rick shows bits of found footage of San Francisco while the audience calls out things they recognize; there’s a kind of collective glee both in inhabiting an unfamiliar perspective on the familiar and in the combined ability to pick out specific things. My reaction to these photos was often similar. In one envelope, labeled “Van Ness corridor,” I found a photo of Hippo Burger, a long-gone burger chain that my dad once told me about going to as a kid. As he told it, they had an item on the menu called “the Cannibal,” an entirely raw burger that my grandma would never let him order. The site is now a CVS. Not that I ever doubted Hippo Burger’s existence, but somehow finding a rather deadpan photo of it in a envelope at the Planning Department made the reality of it more palpable.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

There were photos of the Western Addition before redevelopment in the 1960s, of the Fleishhacker Pool building when it was already abandoned but before it was destroyed by a fire, and of the Apollo Theater in the Excelsior (which was known for showing Filipino films) before it was turned into a Walgreens. In the photos of the Apollo, it’s already empty: instead of the names of movies, the marquee reads “for rent,” and lists the address and phone number.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

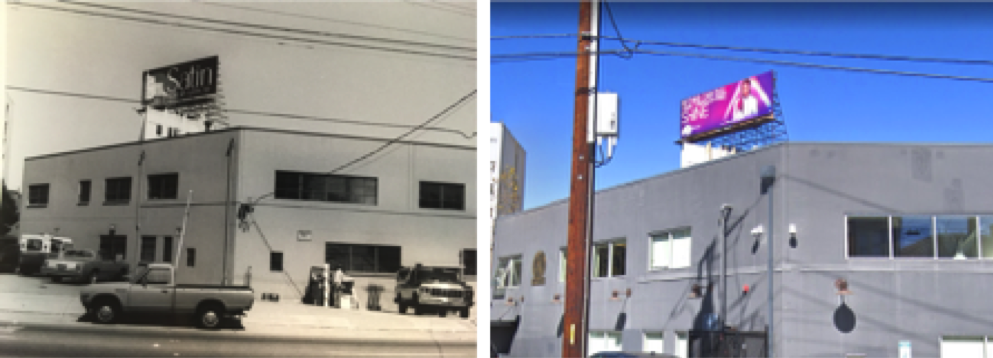

More than specific buildings, there were the fleeting textures of fashion and advertising. In an envelope labeled “City of Paris” (a now-gone department store), a woman strides past the camera with big hair, sunglasses, and amazing striped bell bottoms. The billboards in the older photos are full of ads for cigarettes and forgotten brands of hard liquor. In a photo of an industrial building near Guerrero and Market, a billboard for Satin cigarettes towers in the background; when I looked up the location on Google Street View, the billboard was now an ad by This Free Life, an LGBTQ-focused anti-smoking campaign.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

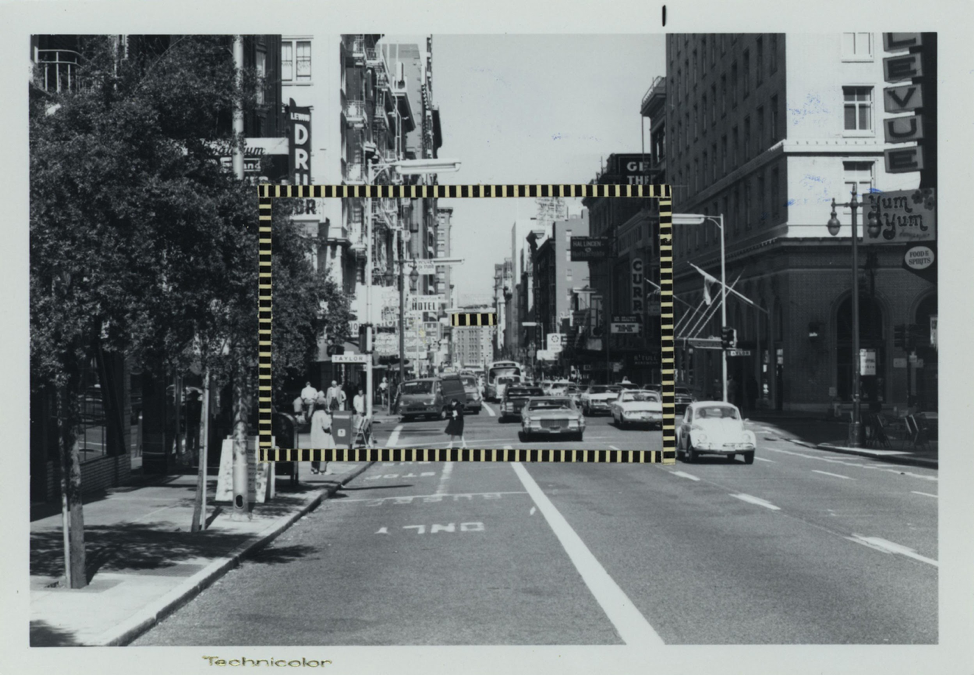

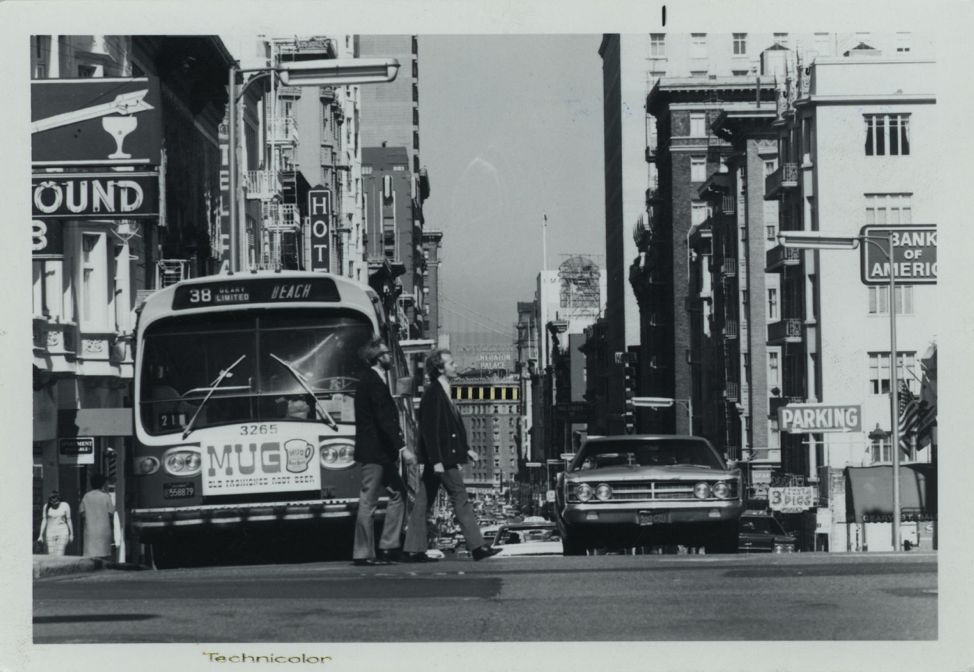

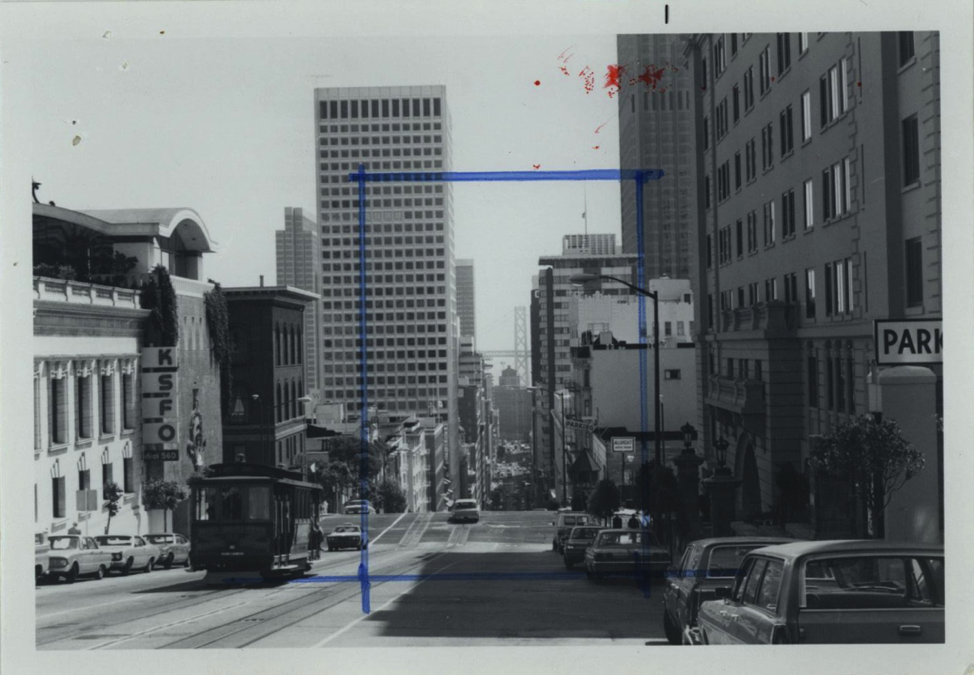

Somewhat overlapping with inadvertently historical photos were the photos of unintended aesthetic interest. For someone who was raised at the end of the film era, this often had to do with artifacts of the photographic process—even 1998 photos had a kind of supersaturated color I now find unfamiliar. Other times it had to do with Planning-specific interventions. One envelope contained images of downtown with various rectangular markings or a kind of striped tape on the photos, presumably something to do with height limits. But for me, I couldn’t look at them without thinking of the photographic interventions of John Baldessari.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

In the neighborhood survey photos, I sometimes found myself inexplicably fixated on certain characters, going about their business unaware that their images would end up in a drawer at the Planning Department. For example, I especially prized a photo of a man in a blue-blue jacket and sunglasses biking determinedly up Grant Avenue in Chinatown sometime in 1998. When I tried to explain it to others, I could only describe it as “a film still from a movie I would like to see.”

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

This “film still” quality was something many of the photos possessed in excess of their function as information. Presumably taken in order to capture generalities (about a place), many of them nonetheless contained the “punctum” that Roland Barthes describes in Camera Lucida: “that aspect (often a detail) of a photograph that holds our gaze without condescending to mere meaning or beauty.” There was something arresting in the photos, having to do with the ineradicable specificity of the people, the time, and the place—things that had happened, had not yet happened, were about to happen. In one photo of people in Portsmouth Square, one man is laughing at something just said, and another looks at the camera, face partially obscured by an exhalation of smoke.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

Because many of the photos weren’t intended to be of anything or anyone in particular, they reminded me somewhat of Georges Perec’s 1974 book An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris. Perec visited the same square in Paris on multiple days, documenting everything that happened with the cadence of a police blotter:

It is 1:35pm. Groups, in gusts. A 63. The apple-green 2CV is now parked almost at the corner of rue Ferou, on the other side of the square. A 70. An 87. An 86.

Three taxis at the taxi stand. A 96. A 63. A bike courier. Deliverymen delivering beverages. An 86. A little girl with a schoolbag on her shoulders.

Wholesale potatoes. A lady taking three children to school (two of them have long red hats with pom-poms).

There is an undertaker’s van in front of the church.

A 96 goes by.

In the introduction to the book, Perec writes that many of the things in Place Saint Sulpice had already been noted. What he was interested in documenting, instead, was “that which is generally not taken note of, that which is not noticed, that which has no importance: what happens when nothing happens other than the weather, people, cars, and clouds.” Details and moments that Perec would refer to as “infra-ordinary” emerge within the frame of the Planning Department photos. In one whose subject seems simply to be “a corner in North Beach,” we see Vesuvio, a historic Beat-associated bar from 1948, with a man gesticulating wildly on the second floor, two people sharing a smoke break, a man painting a picture of the building across the street, roadwork recently patched over, and a campaign sign for a San Francisco Superior Court judge who would pass away just one year later.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

Eventually, I found that what I was really looking for was something like the “infra-temporal”: moments of uncertainty, instability, contingency, and transition that erupted like bubbles within the seamless experience of history. It turns out that, in many ways, the archive selected for this type of image, since besides the neighborhood surveys, the occasion for taking a photo was often that something was about to be torn down, renovated, replaced. The effect was destabilizing: occasionally I’d find things like a hole in the ground where some now-familiar building stands, or the enormous Pioneer Monument being moved from in front of City Hall to its current location closer to Civic Center.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

Occasionally this quality of contingency surfaced within the photos themselves. In a stack of fairly straightforward photos, there would be a few mistakes that were strangely beautiful, like the unknown man disappearing down a blurry hallway. A few photos of Petrini’s, a former local grocery chain, were awash in a gradient of blue, magenta, and yellow that somehow seemed to presage the store’s slide into nonexistence.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

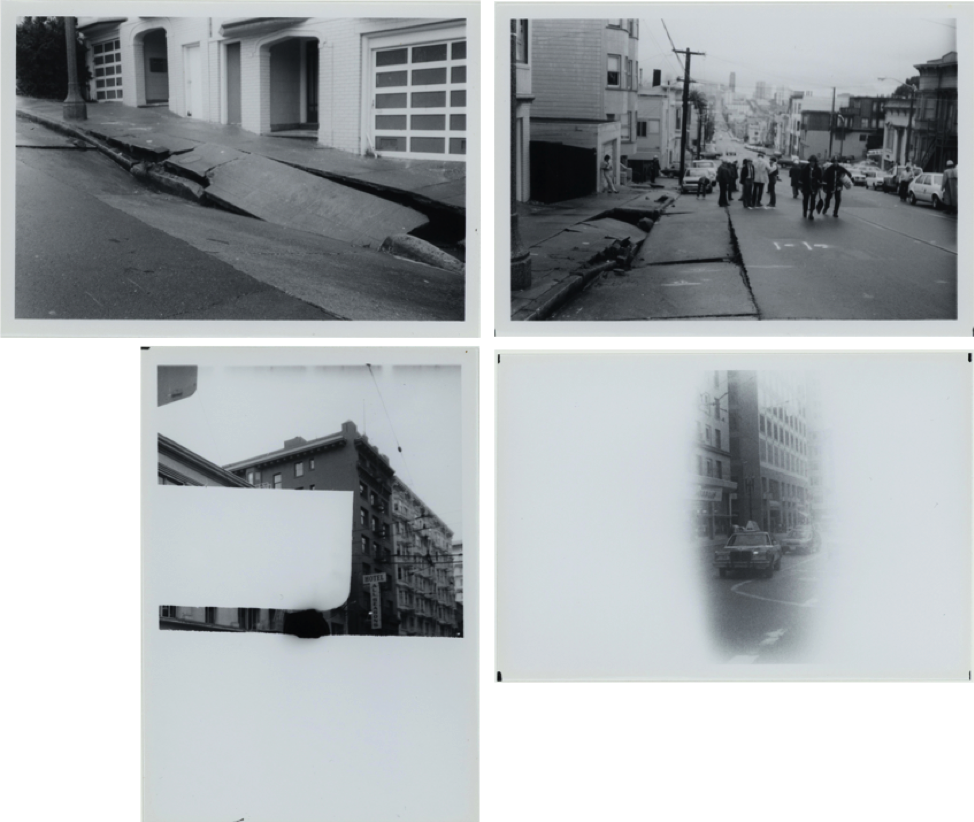

In an envelope from the 1960s, I found people responding to part of a sidewalk that had caved in. Some error has interrupted the development of some of the photos, leaving fragments of unfinished images on a white background. It’s as though the rupture in the concrete had happened in the film processing itself.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

One of my favorite envelopes contained photos of planners visiting Lake Merced Hill in the 1960s. In one photo, they stand with their arms crossed, surveying the scene; in another, they’ve unrolled their plans onto the grass and are poring over them while looking back at the land; in yet another, a planner stands far away next to the trees, looking very small.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

These particular photos are an illustration of something I had noticed in my time at the Planning Department, especially in the conversations I had with planners and the meetings I attended. It wasn’t just the human effort involved in planning what becomes, for everyone else, part of the given everyday. It was the curious position of the Planning Department, which has to both act and observe, build and amend, propose and respond. It has to act anew within the constraints of what is already there, including decisions made by other planners. And it must acknowledge unpredictability, since its plans ultimately play out in a capricious human field of use, opinion, and desire.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

That’s why, whatever neighborhood surveys the 1998 photos might originally have been made for, I became so interested in how people were pictured in them. Initially the subjects in the photos reminded me of people on Street View, those passively captured inhabitants of urban space whose identities hover somewhere between the specific and the generic. However, the relationship between photographer and photographed is more complex here. These were not taken by a machine but by a person, another resident of San Francisco, whose job it was to affect the spaces through which the subjects moved. When one of the people looks back at the camera, it’s not only the subject looking at the photographer but the inhabitant looking back at the planner.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

Besides Street View people, the subjects of the photos also initially reminded me of the “render ghosts” of architectural plans, those placeholder people often shown streaming peacefully through future shopping centers and bayside parks. For instance, when I found a photo of two people sitting in landscaped parklet, it seemed they were included to show how people use the space. But temporally speaking, the people in the parklet couldn’t be more different from render ghosts. Instead of proposed, generic people in a future space, they were real people who actually were in an existing space.

When I decided to make a book of the photos, I called it Living in the Archives. I was referring not only to myself, living amid the boxes and files, but these real people—sitting, chatting, walking, and smoking in the drawer’s envelopes. Whether they knew it or not, their activities in some way constituted the content of the city.

Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department

A funny thing happened to me after a few months at the Planning Department. Whenever I would go for lunch, I would have to cross the intersection of Mission, Van Ness, and Otis. The intersection was a chaotic jumble and the light was long, so I had a lot of time to contemplate the scene across the street: a giant hole in the ground with a crane towering overhead. On Mission, you could peer through holes in the temporary screen and see men moving industriously amid piles of materials. Sooner than it seemed, the building would be finished; it would in fact be the new home of the Planning Department. But after hours in the windowless archive room, sorting the photos into piles on the lid of a recycling bin, emerging into this blustery scene came increasingly to feel like entering another photo from the archive. And I was its unwitting subject: walking to lunch, somewhere between the past and the future.