Composite image of the 1938 Works Progress Administration Scale Model of San Francisco by David Rumsey and Beth LaBerge.

By Gray Brechin

This article was originally published in Calafia, the journal of the California Map Society and used with their permission.

A startling message landed in my inbox ten years ago from a University of California employee overseeing the move of artifacts from a Berkeley warehouse to another warehouse in Richmond. Tamara Garlock wrote: “ We found a 1935 scale model of San Francisco originally created for the 1939 World’s Fair at Treasure Island” which, she said, was stored in sections in sixteen wooden crates. Ms. Garlock had contacted me because she thought that, as the Project Scholar for the Living New Deal, I might have an idea of an alternative home for the model. The University recognized its value but also needed the considerable storage space those crates were taking up in order to hourse its immense Anthropology Museum collection.

A photo I discovered at the National Archives showed the model when it debuted at City Hall in 1940. A caption said that it was 37 X 41 feet, so that if all 1517 square feet of it was reassembled, I thought, it would offer an invaluable freeze-frame of what the city looked like just prior to Pearl Harbor — sand dunes, truck farms, cemeteries, lumpy topography, and all.

Model at City Hall unveiling, April 1940. Photo courtesy WPA, San Francisco Department of City Planning Records (SFH 465), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

When I visited the Berkeley warehouse amidst the move, I found what appeared to be hundreds of sections of an immense wooden jigsaw puzzle, grey with decades of dust, stored on racks in giant wooden crates that had been specially built to hold them. Yet these were not the entirety of the model since, I learned, about a third of it — the NE section of the city — was intact in a locked room at the College of Environmental Design. There, it had chiefly been used to do shadow studies of new downtown high rises.

I contacted the San Francisco Chronicle’s Carl Nolte, who visited the model at its new lodging in the Richmond warehouse and wrote a column about it in 2010. When no one stepped forward to take it, the Chronicle ran a follow-up editorial, with similar results; all public spaces large enough to accommodate such a behemoth, it seemed, must now be kept available for fundraisers.

The model was the idea of prominent architect and Art Deco master Timothy Pflueger, who noted, in 1935, that no comprehensive plan of the city had been done since Daniel Burnham’s visionary scheme of 1905-6. Recent developments during the Depression, such as the new Golden Gate and Bay Bridges, portended radical changes to the city’s layout that required a new master plan. “A large scale model of the entire city is indispensable in the study of the problems because of our hills and valleys,” Pflueger said. “No one can visualize the city from a flat map. The model should accurately show all natural topography in undeveloped areas, grades of existing streets, lot sizes, and developments.” Moreover, it would provide work during the Depression “for architectural and engineering draftsmen, men of various crafts who would work on the model and others who would gather and compile the data.”[1]

Work it did provide, for the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA), under the sponsorship of the Planning Commission, put 300 employees to work on the project for more than two years at a cost of over $102,000 (almost $2 million today). During 1200 man-months of labor, they worked from field observations, a variety of maps, and a 1938 survey of the city by aerial photographer Harrison Ryker,which enabled them to include even small outbuildings in the centers of blocks that were invisible from the streets. Built of poplar and sugar pine at a scale of one inch to 100 feet, the tallest point in the city — Mount Davidson — rose more than nine inches from the common base.

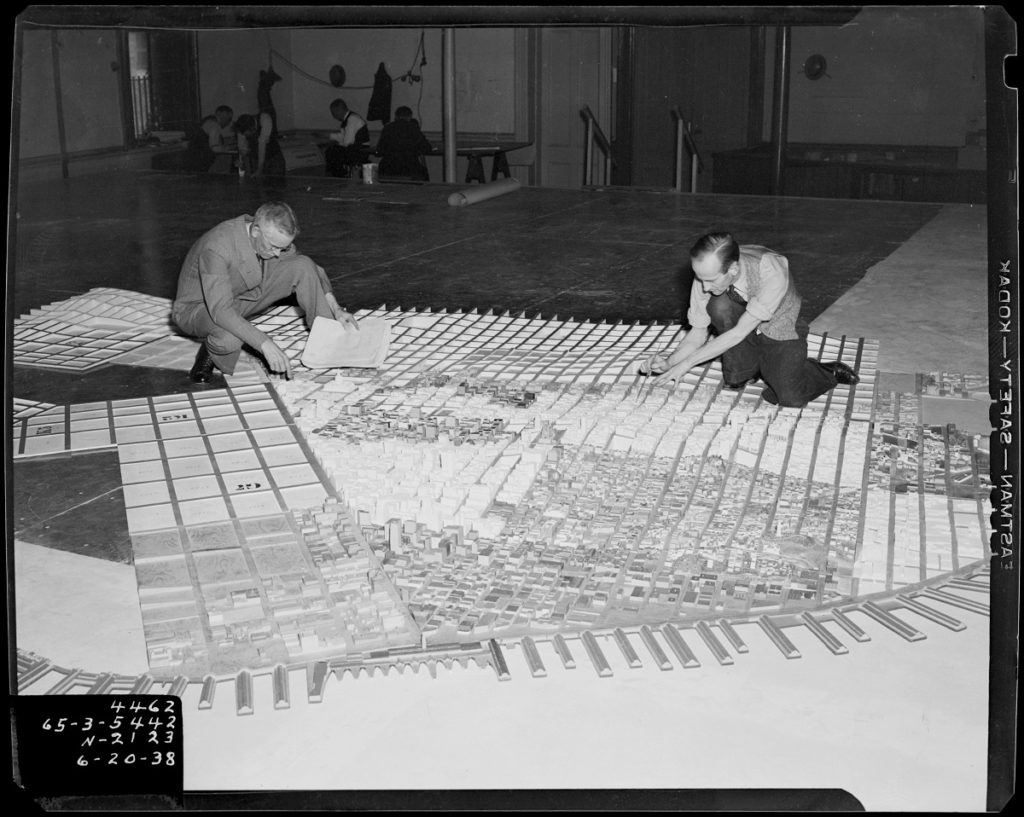

WPA workers assembling the model, June 1938. Photo courtesy WPA, San Francisco Department of City Planning Records (SFH 465), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The model itself consists of 158 sections, whose streets provide a stationary grid for about 6000 removable city blocks upon which workers mounted tiny representatives of structures present at the time of the model’s construction. On the city’s most extreme topography, the ingenuity of the construction is revealed when the blocks are lifted off the armature. They were designed that way to be updated to anticipate or correspond with changes in the city’s fabric.

The NE quadrant of the model — the historic city’s nucleus — was apparently finished first and put on display at the 1939 World’s Fair on Treasure Island, probably before the outermost neighborhoods were completed. The entirety was dedicated in the City Hall’s Registrar of Voters room on April 16, 1940, but remained on display only until the beginning of the US engagement in World War II, when Mayor Rossi ordered it crated and stored to make room for the Civilian Defense Administration. From that point on, it was lost to the public as an educational tool.

The San Francisco Planning Commission and Redevelopment Agencies occasionally used sections of the model for planning purposes, updating neighborhoods such as the Western Addition and South of Market as urban renewal projects bulldozed them. At some point in the 1960s, it was transferred to Berkeley and U.C. ownership. The NE quadrant was kept intact for planning purposes at the College of Environmental Design’s Environmental Simulation Laboratory, while the bulk of it was consigned to storage in the original wooden crates, and largely forgotten.

I had given up trying to find a home for the model when the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Curator of Public Dialogue, Deena Chalabi, arranged a lunchtime meeting with a Dutch couple in October, 2017. The artistic team of Lisbeth Bik and Jos Van der Pol (Bik Van der Pol) work around the world, and were then looking for a project in San Francisco that would, they hoped, engage people in civic dialogue about the city’s development at a time of unusual stress due to the radical changes attending the tech boom. Chalabi, whom I had told about the orphaned model, suggested that I share this Bik and Van der Pol as well.

Within months, and with the imprimatur of the SFMOMA and the San Francisco Public Library, Bik Van der Pol set in motion the transfer of the model from its two non-public venues in the East Bay to a spacious and well-lit warehouse space in San Francisco’s South of Market district. The complicated move, and all details of cleaning, preservation, documentation, and the organization of the constituent sections of the immense model were masterfully marshaled by Chalabi’s assistant Stella Lochman – a most fortuitous choice, since she possesses an encyclopedic knowledge of, and infectious enthusiasm for, the city in which she has lived her entire life.

San Francisco’s billowing topography and microclimates have made it a city of distinct neighborhoods from the start. Bik Van der Pol planned to capitalize on those “villages” within the city by distributing the model’s component sections to the city’s 27 branch libraries, where they would be displayed in plexiglass cases from January 25 to March 25 of this year. Their project — part of the Museum’s Public Knowledge outreach program — is known as Take Part and asks the question “Is there room in San Francisco for San Francisco?” Intended to encourage discussion and community, it has done precisely that in an ambitious two-month sequence of talks, bike tours, movies, and panel discussions orbiting around the still-fragmented model. However, both discussion and community actually began among those who answered Lochman’s call for volunteers in the summer of 2018. As they meticulously brushed, vacuumed, and sponged away decades of grime, the volunteers not only revealed minute details and subtle coloration, but communed with the nameless workers who had built the colossus eighty years before. Just as Tim Pflueger had intended, the model taught them to see San Francisco’s neighborhoods in a granular detail that none had ever experienced on foot, bicycle, or car, and that no flat map, or GoogleEarth view, could match.

David Rumsey took an interest in the model from the moment he saw it in storage at the Richmond warehouse. With the help of Beth LaBerge’s high-resolution photographs of all sections of the model after its cleaning, as well as the 1938 aerial survey used by the WPA workers, Rumsey stitched together a composite image of the entire model with metadata and supporting information, such as archival photographs provided by the Public Library’s San Francisco History Center, as well as contemporary images. Although no permanent home has yet been found for the model in its entirety, one can visit it on Rumsey’s website where prewar cartography meets that of our own time.

The Living New Deal has evidence that WPA workers built other city models as well as many of the topographic models one still sees in national and state parks. A movie titled “A Better New York City,” for example, shows the workers creating a model of that city (not the giant model of the five boroughs that Robert Moses had built for the 1964 world’s fair that is now the star attraction of the Queens Museum), while the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History displays a detailed model of that city’s downtown before redevelopment, which is just part of a larger whole. Our hope is that the excitement generated by the San Francisco model’s resurrection will not only find it a permanent home, but reveal other models, long consigned to dust in basements and warehouses. Such models offer hard copy, three-dimensional glimpses of how U.S. cities looked eighty years ago even as the work of those employed by the WPA and other New Deal agencies helped lift those cities out of the Great Depression that had frozen their development for much of the thirties.

Dr. Gray Brechin is Project Scholar of the Living New Deal — an ever-growing team effort to identify, map, and interpret the public works legacy of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal — hosted by the U.C. Berkeley Department of Geography. He is the author of Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin (U.C. Press, 1999 & 2006.)

[1]Unsigned, “Pflueger Favors New Plan,” Architect & Engineer, 121:3, 60 (June, 1935.)