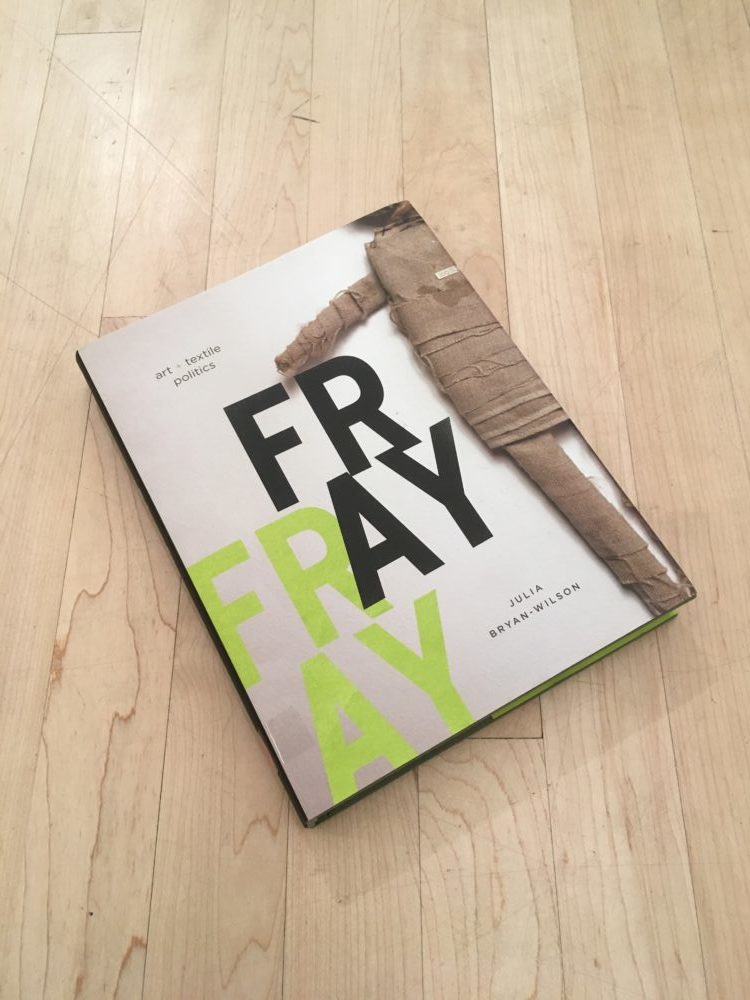

Photo courtesy of Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson is a professor of modern and contemporary art at the University of California, Berkeley; the director of its Arts Research Center; a curator; and the author of several books, including Fray: Art and Textile Politics (2017). She recently curated the exhibition Cecilia Vicuña: About to Happen, at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA). A longtime collaborator with SFMOMA, Bryan-Wilson is a Public Knowledge scholar and a proponent of the idea that knowledge is found outside the economic frameworks that regulate society. She was interviewed by journalist Sophia Fish from the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.

SOPHIA FISH: You are the director of the Arts Research Center (ARC) at UC Berkeley. What is ARC, and what role does it serve on the campus?

JULIA BRYAN-WILSON: The Arts Research Center is an interdisciplinary think tank for the arts; it’s a hub for scholarly explorations about the arts (visual, written, and/or performed) in the most widely defined terms. One of our missions is to foster and promote conversations about artistic practices among our faculty and students, both undergraduate and graduate. We also have a more public-facing component, where we host events, including conversations, workshops, and symposia, with distinguished guests—including artists, curators, and academics—from all over the globe. In general, we aim to foster arts research on campus while also making visible the impact of the arts in a wider political realm.

SF: This relates to the idea of Public Knowledge at SFMOMA—of trying to make knowledge more accessible, and challenging the idea that there should be keepers of knowledge. From your perspective of arts research, why is public knowledge important?

JBW: One of the ways I define public knowledge is as a network of circulation outside of elite markets, or as a flexible system of alternative distribution that is not mediated by private economic interests. The arts are an extremely broad set of grammars or vocabularies or forms that are produced by many different kinds of makers and that do not only exist for refined audiences. Grappling with this full scope of artistic creation in is vital, and the notion of public knowledge is very useful for thinking critically about all these circuits of exchange. This past year our programming emphasized that arts research doesn’t always take the shape of traditional scholarship. It doesn’t always fit within an academic envelope. For instance, choreographing a dance is also a method of sensorial or tactile research; if you are learning how to sew in order to construct your own outfits, you are enacting arts research. Over the course of 2017–18 we held a series of events that honored research with a more embodied approach.

SF: Can personal art-making or hobbyist art-making be a form of public knowledge? Does it always have to be shared?

JBW: That’s a complicated question, because some hobbyist creations may not circulate beyond the home; these are items created for someone’s private pleasure—yet often they are produced based on community-based pedagogies that are transmitted via family or friendship, which means that absolutely they partake in public knowledge. And much amateur making comes out of, and generates around, informal networks of display and exchange that provide spaces for sharing, like local quilt shows. In many contexts, extremely sophisticated knowledge about advanced technique spreads through word of mouth and extra-institutional personal contact.

This past spring I organized a major symposium entitled Amateurism Across the Arts, which was dedicated precisely to thinking about do-it-yourself artistic production in music, literature, visual art, new media, and fashion. The speakers and performers interrogated how hobby making has been an enormous motor of innovation. It is also vital to think about how DIY art is often created polemically to exist outside of a capitalist framework, because a lot of those homegrown efforts are not interested in participating in economic exchange.

SF: Amateur art, then, can be thought of more as public knowledge than knowledge created within those capitalist frameworks of power.

JBW: Right, because there’s not a gatekeeping mechanism about certain specialized regimes of training and display. The museum is not the only place where people get inspired—sometimes it is, and of course a big part of what I do is study objects in museums, but art history has been woefully neglectful of many aspects of artistic making that might not ever reach—or only in very exceptional cases reach—the taste-making realm of so-called “fine art.”

SF: Do you think there is a need for some way to sift through it all, or to edit? Is there a need for someone or some mechanism to determine what gets selected and circulated—as in, how historians select which aspects of history get written in books, or curators select what appears in museums?

JBW: Debates about quality, and about classifications of “good” and “bad” or other hierarchies of taste, are extraordinarily loaded; they have always been tied to class, to race, to gender, and also to sexuality, region, age, and ability. There are so many ways that those categorizations are interlaced with privilege and exclusion. For me, it is productive to imagine a far more leveled system of attention, one in which both the purportedly marginalized and the most recognized are given due attention.

I am interested in acknowledging many different kinds of taste, many different judgements about what quality is. When there is only one standard or template forced onto everything, it inevitably benefits the same few artists, usually white male artists, who have always benefited.

SF: How does feminist theory contribute to public knowledge, how do they inform each other?

JBW: Everything I just articulated about dismantling hierarchies of “greatness” is indebted to intersectional feminist theory, critical race theory, and queer theory as they rethink the exclusionary dynamics of the canon itself. There are not just a few people who hold the keys to all the wisdom surrounding literature or art or music. The idea that there could be a more democratic or populist set of criteria, where all kinds of people are authorized to make work, to evaluate work, and to circulate work—that, to me, is very feminist, and feels like part of the public knowledge impulse.

SF: In your recently published book, Fray: Art and Textile Politics, you give case studies of the ways the politics of textiles and sewing have been upended to change how they are tied to the organization of social contracts that play out in the home and in the workplace. How did you come to choose the very particular art practice of textiles as your subject?

JBW: There are many origin moments for that book: one of them is that I came to textiles in part as the daughter of a feminist sewer. My mother’s generation of 1970s feminists included some who rebelled against the imperative to do the “women’s work” of sewing and knitting, but others, including many feminist artists, who were interested in reclaiming textiles—artists like Miriam Schapiro, for example, with femmage, or Howardena Pindell with her cut-and-sewn paintings.

My mom is not an artist, and when I was a child in a small town in Texas, we had nothing to do with the art world whatsoever, so it’s not as if she was steeped in these debates. But she was a very proud sewer, and she made a lot of my family’s clothes. We were quite poor, and in those days, before the saturation of fast fashion, it was cheaper to make clothes than to buy them, so I grew up surrounded by sewing machines and going to fabric stores. She was also a very outspoken feminist, and these things were not, in her mind, a remote contradiction. She happily performed the duties of women’s labor in the domestic sphere, in part because they came out of need and necessity.

Within modern and contemporary art history, textile work has frequently been stigmatized. This stigma may have fully eroded by now, but it was definitely still in place when I was in graduate school. Handicraft by women was lower or lesser than, and not worthy of consideration. Given my queer, feminist, and Marxist investments, I wanted to contest that marginalization, as many feminists have done before me. It was also a natural, organic outgrowth of my previous book, Art Workers, which is about artist labor, because textiles, too, raise questions about process, work, materiality, intimacy, politics, and value.

Another origin moment was that I had a formative encounter with the Chilean appliques called arpilleras when I spent a semester abroad in college in Santiago, Chile. I had never seen textiles as explicit or as hard-hitting as these, and they really made an impact on me. In some ways, the whole book stemmed from my attempt to reckon with the arpilleras, to build a scholarly and a theoretical context in order to situate them within my own research trajectory.

SF: In 2014 you helped organize the Visual Activism symposium at SFMOMA. How do you think visual activism has changed in light of recent feminist movements like #MeToo?

JBW: Artistic production and activist production often converge around questions of the visual—that was one of the starting points for the conference, and also for the special issue of the journal that that Dominic Willsdon and Jennifer González and I coedited (Journal of Visual Culture, 2016). Our phrase visual activism explicitly cited Zanele Muholi, the South African black, queer photographer, and she was one of the conference keynotes, so our entire framing of that concept was from the outset centrally concerned with race, gender, and sexuality. In their most incisive iterations, the visual activisms of our current moment are ones that resist racism and patriarchy and homophobia.

My collaboration with Dominic and Jennifer has proven very generative; I now teach a lecture course called Visual Activism that I developed in the wake of the conference. Instead of organizing the syllabus according to a succession of art movements—from Pop to Minimalism to Conceptual art to performance art to earthworks, for instance—it is organized by social movements. We start with Black Power and Brown Power, and look at the visual activisms associated with the civil rights movement, as well as the women’s liberation movement, gay liberation, Earth Day and the rise of environmentalism, etc. In fact, we study much of the same art, but because the time period of the 1960s to the present is approached through a totally different lens, I also bring in a lot more activist graphics, resistant street art, and demonstrations. It was a fruitful way for me to reformulate how I teach that kind of survey class.

SF: Gender nonconforming art practices within fashion, design, and theater are becoming more mainstream. What is your take on that? Does becoming mainstream and working within the capitalist market dilute the original intention?

JBW: Even back in their heyday, the Cockettes had mainstream coverage in venues like Rolling Stone. Many people—countercultural and not—were fascinated by them. On the one hand, it’s great when marginalized phenomena get exposure, because they become inspirational for isolated queer folks who previously felt like they were alone in the world. The cynical version is that the hegemonic order wants to unearth every subcultural formation to make money off of them. In our current climate, it can feel like many gender nonconforming artistic practices end up in the churning grind of publicity and that there is no place to form your own identity that is not subject to the surveillance of branding and social media.

SF: What’s next for you and the ARC?

JBW: I am going to be away for the 2018–19 academic year as the Robert Sterling Clark Visiting Professor at Williams College, so Natalia Brizuela, who works in the departments of Spanish and Portuguese studies, as well as in film/media studies, is going to be taking the lead. She is working with a team of collaborators who have been awarded a University of California Humanities Research Institute grant to put on a series of events about political art from the global south. I’ll be teaching two seminars and also finishing my next book, which is about the sculptor Louise Nevelson.