Lillian Saunders is a sophomore at the University of San Francisco majoring in Urban Studies. She wrote this blog post for Professor Rachel Brahinsky’s Urban Field Course, which visited several sections of the WPA model in Spring 2019.

I moved to Ingleside from the Fillmore when I was five years old. Located in the southwestern section of the city, Ingleside is a largely residential neighborhood that sits on top of a valley between Mount Davidson and Daly City. My parents had never heard of Ingleside prior to moving, let alone thought about moving there. Even now when I tell people where I live, the best I can expect is a hesitant nod and more often a blank stare. It’s “a city that few tourists ever see” (Walker 1995).

I take pride in my secret little corner of San Francisco (see fig. 1). I recently went to view the WPA model of Ingleside at the library in order to gain more historical perspective on the area (see fig. 2 & 3). The model is a physical representation of the layers of city change due to cycles of capital investment that we have witnessed on each of our walks. As we observed downtown, the architecture of buildings can be read as a sign of when and why capital was invested into an area.

Ingleside was mostly farmland until 1906 when the area served as a refugee camp for those displaced by the earthquake. By 1936, most of the homes in my immediate area were already built, although there were vast tracts of land to the south that were still undeveloped. Farmhouse-style homes were scattered throughout more recent standard box houses. As more demand for housing in San Francisco grew and more investment came into the area, houses began to occupy each lot of the neighborhood, creating miles of suburban-style homes that “appear banal, [but only] because we are so completely inured to its distinctiveness as a form of human habitation” (Walker 1995).

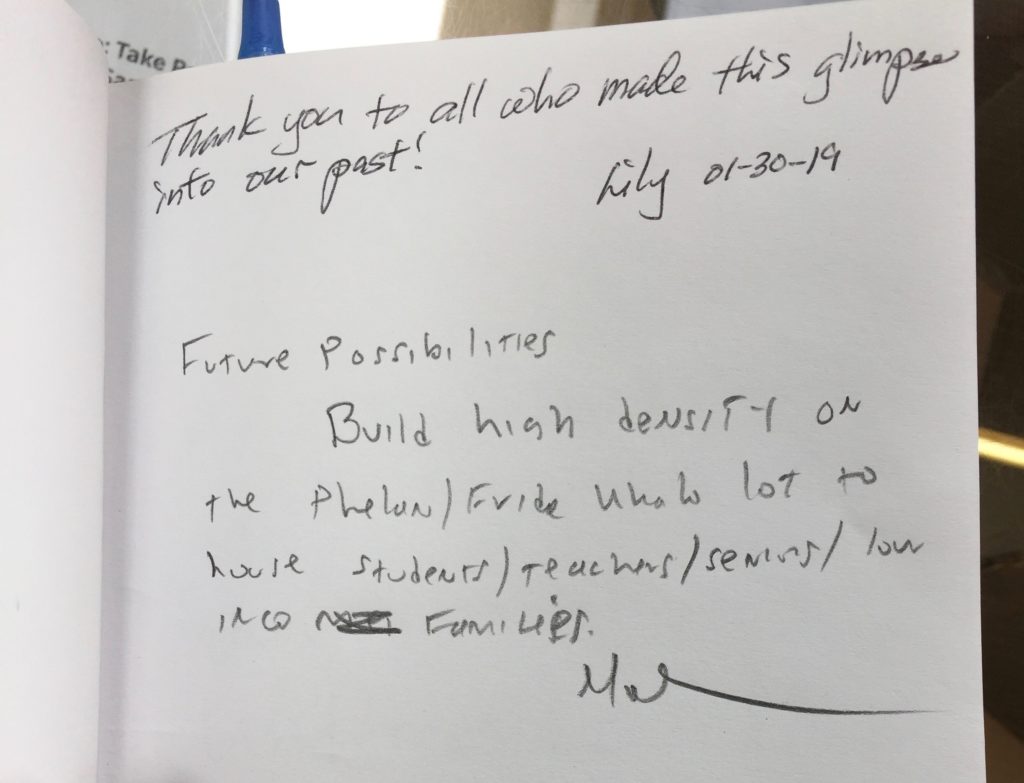

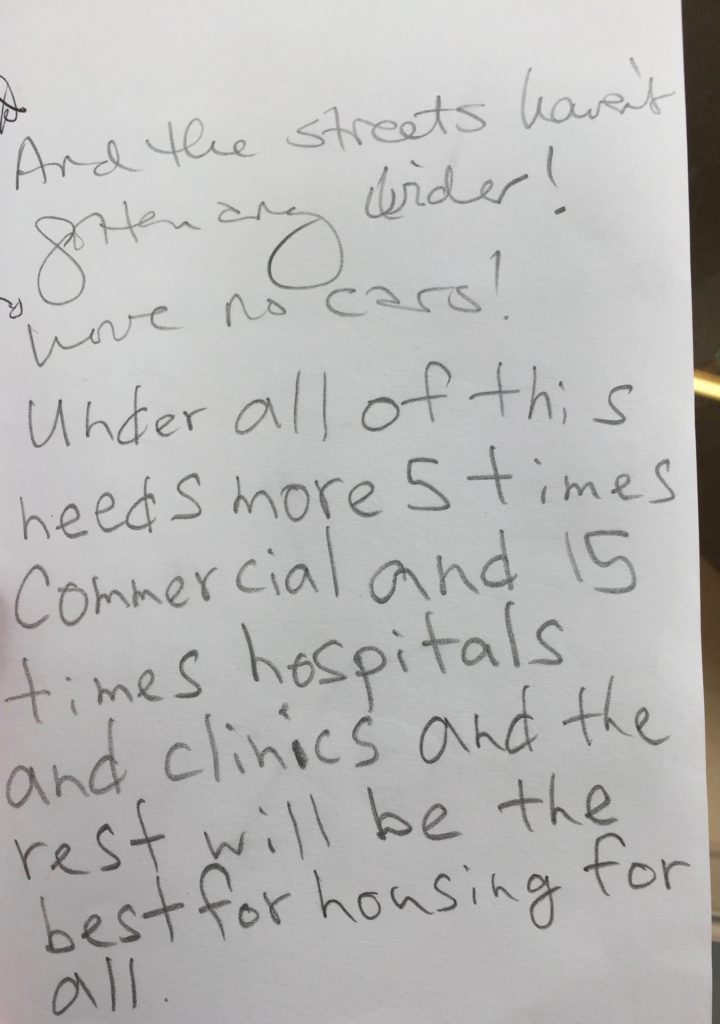

The WPA model gives residents the power to see the city from a perspective they’ve never witnessed before. When viewed from above, the “elevation transfigures [the viewer] into a voyeur. It puts him at a distance. It transforms the bewitching world by which one was ‘possessed’ into a text that lies before one’s eyes” (de Certeau 1984). The model allows viewers to view the city objectively as a “text” outside of the constraints that are present when observing from ground level. The temporary, moveable nature of the model buildings provides viewers with “perspective vision and prospective vision [that] constitute[s] the twofold projection of an opaque past and an uncertain future on to a surface that can be dealt with” (de Certeau 1984). It inspires viewers to see the city as a constantly developing surface where nothing is definite and everything can be improved in the future, as evidenced by the comments left by visitors (see fig. 3 & 4). The model serves as a reminder that positive change is internally motivated and starts with us.

Figure 1. My corner. Section of the 1938 WPA model. Image from https://www.davidrumsey.com via https://boingboing.net/2019/01/08/public-knowledge-take-part.html

Figure 2. Ingleside neighborhood section of the 1938 WPA model. Image from https://www.davidrumsey.com via https://boingboing.net/2019/01/08/public-knowledge-take-part.html

Figure 3. San Francisco 1938 WPA model. Image from https://www.davidrumsey.com via https://boingboing.net/2019/01/08/public-knowledge-take-part.html

Figure 4. Notes left by visitors to the WPA model at the Ingleside branch of the SF Public Library. Photograph by author, Spring 2019.

Sources

de Certeau, M. (1984). The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Walker, R. (1995). “Landscape and City Life: Four Ecologies of Residence in the San Francisco BayArea.” Ecumene, 2(1), 33–64