by Deena Chalabi

Deena Chalabi is a curator and writer, and currently a Visiting Scholar at the Arts Research Center at the University of California at Berkeley (2019-20). Previously, as the Barbara and Stephan Vermut Associate Curator of Public Dialogue at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2014-2019), she co-curated Public Knowledge, a multifaceted initiative funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities that invited the public, through free exhibitions, events and publishing, to participate in expansive and critical conversations about urban change and knowledge in the digital age. In this essay, she explores some of the core ideas that sparked the initiative, animated the core partnership with the San Francisco Public Library and underscored the numerous collaborations with artists, scholars and many other individuals and organizations in the Bay Area and beyond.

Public Knowledge, with its many facets, projects, activities, events, and voices, has been a way to combine multiple ambitions related to reigniting civic imagination. The seeds began to germinate in 2015, when education and public practice curator Dominic Willsdon and I were developing plans for SFMOMA’s reopening. The expanded building was to have two additional entrances as well as many new windows with views over San Francisco, a city in the grip of its own processes of redefinition. Could the museum’s increased architectural porousness, we wondered, expand its sense of openness to the world beyond its walls in other ways? With a series of artist commissions and free public programs, through research and experimentation in collaboration with artists and others, could we foster community engagement and respond to the changing urban context by reimagining what is possible?

We developed Public Knowledge to invite reflection on the technology industry’s impact on the city’s economic and physical landscape, to better understand how the changes sweeping the city affected the ways individuals and communities could access one another, build social infrastructure, retain cultural memory, and participate in civic life. We wanted somehow to take account of the palpable increase in inequality and the resulting sense of crisis among those facing eviction, displacement, or erasure, and to connect this issue of heightened urban change to the ways that knowledge had been transformed in the digital age. It was an opportunity to evaluate the role of a cultural institution like SFMOMA in the public life of the city, and to ask about its responsibility not just to collect and display artworks but also to facilitate constructive and critical dialogue among communities.

In order to unpack these many complex and interconnected issues, the Public Knowledge team worked in interdisciplinary ways, combining perspectives and considering our activity within a broader ecosystem of contemporary knowledge production and cultural work. We took the time to nurture dialogue and collaboration with organizations and individuals who not only shared an interest in the project’s questions but also shared its values: the importance of the arts and humanities for fostering critical thinking and empathy, and, in turn, the importance of critical and empathic public dialogue for strengthening democratic processes, and building an inclusive city. At the core of Public Knowledge is an idea that seemed almost radical in the contemporary Bay Area context: that to succeed at the goal of civic reimagining in an era of constant disruption and disintegration, it might be necessary to privilege maintenance and recovery. Rather than moving fast and breaking things, as Mark Zuckerberg described his approach to building Facebook, we came to recognize the value of moving slowly and knitting things together.

Our first steps involved the San Francisco Public Library. In 2014 Dominic, program associate Stella Lochman, and I had organized an SFMOMA On the Go exhibition, Chimurenga Library, at the SFPL’s main branch; this opened our eyes to the workings of the library and the realities of its location at the convergence of mid-Market and Civic Center, a dramatic intersection where several of the city’s increasingly divergent populations coexisted. Moreover, we had witnessed firsthand the library’s willingness to collaborate, its excellence as an institutional partner, and its potential as a fertile and thought-provoking site for art making and engaging with communities beyond the museum’s. As Public Knowledge scholar Shannon Mattern has written, libraries and museums can be sites for the public in “a rapidly evolving city . . . to understand, and potentially redirect, its transformation.”[1] If Public Knowledge was to be an argument for maintaining and bolstering civic culture, then the museum-library partnership would be both its cornerstone and its method.

In the age of the Internet and social media, when the received wisdom is that all useful information is accessible online and the most efficient ways to communicate are through digital means, museums and libraries have had to evolve and adapt. Inherently slow moving and therefore sometimes considered obsolete, they enjoy high levels of public trust (much higher than media outlets or the government) and have the opportunity to use that trust to strengthen meaningful social bonds. In many ways, the work of the library in particular is a quiet but persistent rejoinder to the disruptive language and actions of the technology industry, with its dominant logic of the market. The library represents the ideal of democratic social capital that is not monetized by private companies, and it serves as a support system for those left behind by underfunded social systems. The defense of libraries has become a political act worldwide, from the human chain outside the Alexandria Library during the Egyptian Revolution to protests across the UK against austerity-driven library closures and petitions to save the New York Public Library from extensive budget cuts. As Zadie Smith has written, the market cannot be a substitute for libraries because the market has no use for the library: “A library is a different kind of social reality (of the three dimensional kind), which by its very existence teaches a system of values beyond the fiscal.”[2]

(Protestors joining hands to protect the Alexandria Library during the Egyptian Revolution. Image courtesy of Bibliotheca Alexandrina Library. https://www.bibalex.org/en/MediaGallery/Default/opponentsandsupportersjoinhandsinprotectingthelibrary)

Shannon Mattern has described these values as “access, accountability, balance between openness and privacy, and commitment to preservation and security of information, as well as a healthy skepticism of technology and about [librarians’] own ideals.”[3] The library’s low threshold to entry—always a free indoor public space, actively welcoming, and requiring no purchase—is increasingly rare, and is supported by what one might call its radical hospitality. SFPL’s well-resourced network of twenty-eight physical spaces, which act as vibrant and busy neighborhood hubs “within walking distance of every San Franciscan,” saw more than 6 million visitors in 2017–18.[4] Over the last few years, SFPL has increased its circulation of borrowed materials as well as its number of users, reaching disenfranchised populations often invisible to more commercial entities (approximately 15 percent of San Franciscans are without Internet at home, according to census data).[5]

The branches are sanctuaries, accessible public institutions for people from all walks of life, and their relevance and uniqueness are apparent every day. They provide havens and support for the homeless, they host story hours for families with children, as well as events for many kinds of communities, and more specialized activities including digital literacy training, rights awareness, and media-rich after-school resources for teens. SFPL provides a physical as well as an online infrastructure, offering information, guidance and tools (both material and immaterial) to job seekers, students, recent immigrants, seniors—those on both sides of the digital divide—for individual exploration and inquiry as well as community development. For all these reasons, the library seemed the perfect partner with which to respond and contribute to the city’s public life and imagination.

It took two years of discussion to develop the foundations for the museum-library partnership, and to develop tools and language to work together. A great deal of time was spent in building trust between staff at organizations that similarly see themselves contributing to the city’s cultural life but that have different missions, roles, funding structures, and priorities. Working in partnership created opportunities for each entity to bring greater self-reflexivity to its work and examine its own role in the rapidly changing urban environment. Through active listening, regular meetings, and interviews with key SFPL staff, we developed a clear yet multifaceted picture of the work that the library was doing, so that we could amplify that work in different ways. We invited librarians to attend museum tours and events, conducted surveys, and asked for regular feedback about what they would like to see from the partnership.

Another aspect of moving slowly was our commitment to engaging with artists and other collaborators over a long duration. We looked for artists, from near and far, who would be interested in championing the role of the library as a platform for the creation of new social possibilities; artists with a commitment to looking deeply at underlying social structures, who would be able to take the time to make a unique contribution to the goal of strengthening the civic life and social fabric of San Francisco.

As Sally Tallant wrote of her work with the Serpentine Gallery’s Edgware Road Project in London: “Sometimes with these kinds of projects it takes a really long time and sometimes there’s a long period of time where it doesn’t look as if anything is happening. However during that time you’re building relationships and conversations and deepening the research.”[6] This process, in which artists are encouraged to take their time to develop an idea with multiple constituents, can be hard to justify at an arts institution used to the faster temporality of more traditional exhibitions and public programs, and it also tends to require a different level of comfort with publicly sharing process rather than simply a final product. While that in itself was sometimes a challenge, the multiyear period for the development of Public Knowledge as a whole allowed the team and our collaborators to understand better the complexity of the situation we were looking to explore, to listen better to specific needs or concerns, and to develop the approaches necessary for richer collaborations and greater public participation.

The first Public Knowledge artist’s project, Josh Kun’s Hit Parade, launched in the spring of 2017, and a branch of the SFPL opened in the museum’s Koret Education Center in the fall of that year. The goal was to create a hub for Public Knowledge and a place for museumgoers, our SFPL collaborators, and the public to engage one another and have critical conversations. The first downtown branch since 1906, this one held reference-only materials, and its categories of books were limited to topics related to Public Knowledge themes (activism, art, cities, culture, education, technology). It functioned as a space for reflection about the role of libraries generally, and it included a piece of the original card catalogue from the library’s 1917 main branch.

It took another six months to begin SFPL programming in the SFMOMA branch, but once it began, there was scarcely a month without an event led by SFPL staff for the next two years. By June 2019, the Public Knowledge Library had hosted almost fifty free public events, with a wide variety of collaborators and audiences. While community outreach is sometimes considered a supplement to an exhibition or artist commission, in this case it was built into the initiative’s reasons for existing, and it became a core component of the artists’ projects, from the early Hit Parade conversations with select library branches and their patrons (Mission, Western Addition, and Bayview) to the most recent work, across all branches, of Bik Van der Pol’s Take Part.

Library scientist Don Swanson wrote in 1986, before the widespread adoption of the Internet, that to make a piece of recorded knowledge fully public it needs to be retrieved and connected to other pieces of information.[7] That process of retrieval and assembly leads to fresh understandings and new discoveries. As we built relationships and discussed plans with our Public Knowledge collaborators—artists, scholars, librarians, and others—it became clear that for us the idea of public knowledge was not just about the assembly of recorded information but also about the assembly of people and the ideas that they were willing to share with one another. Each artist’s project was a combination of elements that were about the existing public record, but also contained an addition to that record, one that had a community dimension and therefore created new public knowledge.

Josh Kun took music from the SFPL collection as a basis for community events and recorded locals’ stories: a response to SFPL librarians’ desire to have more voices of patrons on the record and in the collection, given the city’s pace of change. Minerva Cuevas combined her interest in fire as the original form of public knowledge and its destructive role in human history with a video exploration, made with Bay Area teens, of the importance of libraries for cities, in Lit TV. Just as their projects took different forms, the artists ended up taking on different roles within Public Knowledge overall. As the first artist to develop a work, and drawing on his previous experience with the Los Angeles Public Library, Kun served as an advising scholar in the early stages. Conversely, Bik Van der Pol’s Take Part, with its myriad contributors, programs, and locations, was in many ways a culmination and a synthesis of approaches and relationships that Public Knowledge had previously developed.

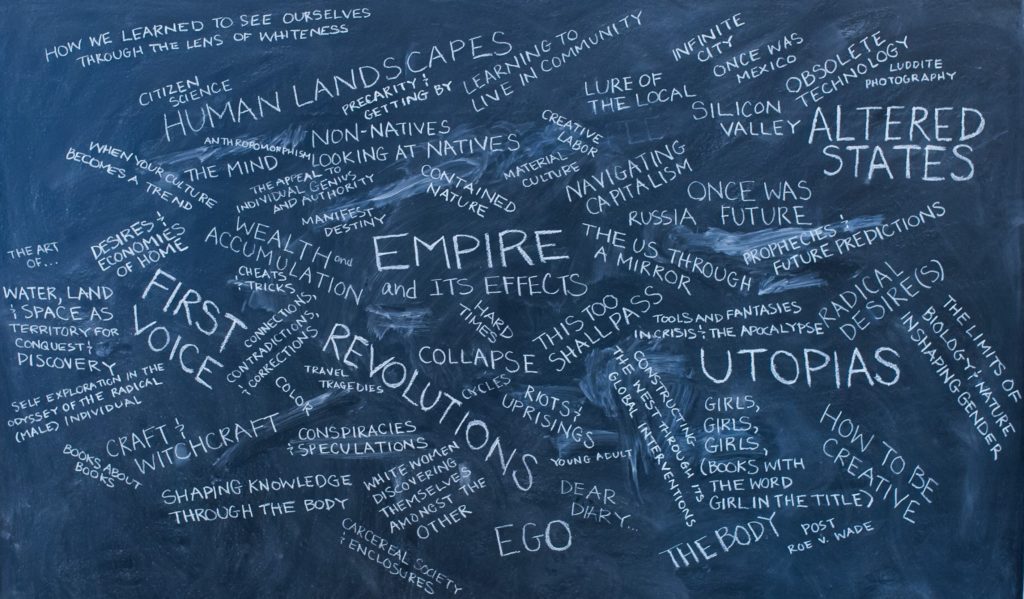

The value of assembly was also at the heart of Stephanie Syjuco’s Added Value project, a used book sale that brought together artist collective Related Tactics and the Prelinger Library team. Together they sorted thousands of low-value books into a new framework with new categories, sparking new ideas (and increasing demand for each object). Growing out of Syjuco’s initial interest in local issues of precarity, Added Value playfully explored the politics behind the categorization of knowledge, and provided a map of the concerns of Bay Area readers. The new categories revealed themselves to be a reflection on San Francisco and the Bay Area, in terms of ideas both to discard and to pick up. Obsolete Technology sat in between Infinite City (stories of SF) and Prophecies and Future Predictions, across the table from Silicon Valley. The Craft and Witchcraft section sat next to Learning to Live in Community.

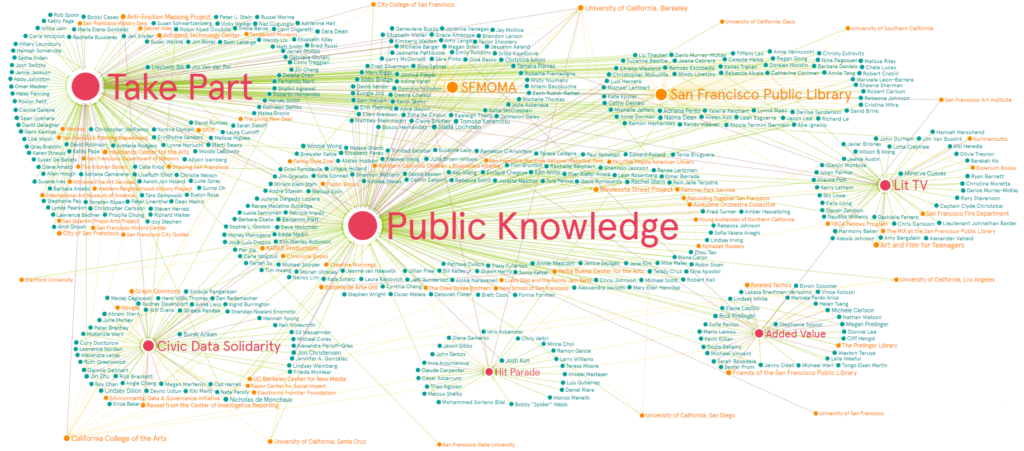

Burak Arikan’s project Civic Data Solidarity had the idea of the network at its core: with a basis in Arikan’s digital network mapping platform Graph Commons, it explored the consolidation of disparate data sets as well as bringing together individuals with shared interests (and sometimes disparate agendas) for workshops to imagine change, around diversity in the tech industry and environmental racism in some of San Francisco’s most marginal neighborhoods. While SFMOMA created a physical space for often difficult conversations, the Graph Commons platform also became a tool to visualize the network that Public Knowledge had built.

The Public Knowledge network was formed and articulated through many conversations, and the public dialogue unfolded in different directions from those, including the evolution of the artists’ projects, public talks, and online articles and essays. We built on existing relationships within and beyond the context of art schools and universities (including but not limited to the University of San Francisco, UC Berkeley, Stanford, City College of San Francisco, California College of the Arts and the San Francisco Art Institute) and involved those working in fields such as architecture, history, geography, media studies, communications, journalism, film studies, and many others. We invited three Bay Area scholars whose work looks at the arts from various angles—Julia Bryan-Wilson, Shannon Jackson, and Jennifer Gonzalez—to participate in the initiative at its earliest stages and provide thoughtful feedback. We engaged scholars from further afield as well, and benefited from the tremendous thinking Shannon Mattern has done at the intersection of data and democracy; Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman’s ideas on sparking public imagination by working from both top down and bottom up; Fred Turner’s invaluable perspective on the unique cultural history of the Bay Area as the crucible for our technological present, particularly through the formation of social networks; and Jon Christensen’s astute observations of all the issues at stake, including in his conversations with Michael Storper on the vital role of Bay Area network building for its current economic formation. We collaborated with artists beyond the core group as well as with numerous additional academics and other practitioners, all known for their skill in knitting disparate ideas together.

(Image of Public Knowledge Graph Commons map. Image courtesy of Public Knowledge.)

The Public Knowledge talks brought our collaborators and other maker-thinker-writers from various fields into conversation with a wider public made up of SFPL and SFMOMA audiences of all ages and backgrounds, and other Public Knowledge events took place thanks to partnerships with entities including the San Francisco Urban Film Festival, Shaping San Francisco, UC Berkeley, and the National Park Service, all with shared values and purpose. These programs engaged a community of people invested in the past, present, and future of an inclusive, diverse, equitable San Francisco (and the Bay Area more broadly) in gathering, assembling, and looking critically at the context in which they find themselves and the issues that matter to them. For the Night of Ideas in February 2019, six thousand people gathered at the SFPL’s main branch for an evening of performance, debate and discussions focused on building critical connections, unpacking frameworks, and resisting the oversimplification of important issues that often occurs when emotionally charged issues about the future of the Bay Area are raised.

The most recent Public Knowledge artist’s project, Bik Van der Pol’s Take Part, imaginatively knitted together the city through the library’s network of neighborhood branches, displaying relevant pieces of a 1930s scale model of San Francisco in every branch and inviting individuals of all backgrounds to share their stories. Not just an exercise in nostalgia or memory or a celebration of the old-fashioned aesthetics of the model, it was also a series of conversations about re-democratizing the city; an acknowledgment of in-person, ephemeral, individual forms of knowledge and experience that make up what it means to live in San Francisco today. From early conversations with multiple generations of researchers and urban planners for whom the scale model had been a research tool, to discussions with communities (for example, in Visitacion Valley) about prospects for future development, the display of the model encouraged discourse and potentially changed the framework of discussions about land use, ownership, and distribution. To knit together past and future requires being present, and “reading the model” was about gathering diverse groups of people to think critically about how urban change has occurred and to explore their preferences for the urban future.

(Stella Lochman leads a discussion about the scale model and the neighborhood around the San Francisco Main Branch Library during the Night of Ideas. Image courtesy of Beth Laberge.)

The outcomes of Take Part, and of the initiative as a whole, are still unfolding, and it is unclear in what ways Public Knowledge has truly been a crucible for the public imagination. While the broader context has changed a great deal between 2015 and 2019, toward even greater individualism, populism, and market fundamentalism, the core issues that inspired Public Knowledge—around inclusivity, equity, memory, information literacy, and community empowerment—remain relevant and in many ways have become more urgent. With its many functions, elements, and ambitions, Public Knowledge explored the idea of the museum as a producer of relationships, partnerships, and nuanced conversations as well as art experiences. It also supported the creation of several tools and resources for civic imagination or cultivating community, including numerous bibliographies and resource lists, and the Public Knowledge Library itself; David Rumsey’s online version of the San Francisco scale model that allows anyone anywhere to explore what the city looked like in 1938, and Related Tactics’ Shelf Life project that can help anyone decolonize their home library and, by extension, their worldview.

“Museums are the last places to think about cultural value, not (just) commercial value. Libraries are the last places to value your citizenship not your wallet,” science fiction writer Cory Doctorow told an early Public Knowledge audience, before asking, “Is the museum a glass case, a coffin of our civilization, or is it a seed pod that we use to build a new one?” Public Knowledge provided SFMOMA with an opportunity to imagine what that seedpod might be. It was an experiment in ways that the museum could function as a public space, that contemporary art could be part of a wider public sphere, and that important broader discussions about culture, ethics, and urban life could circulate back into the museum. At its best, it was a convener of discussions on urgent topics, an important connector of individuals and organizations, and, we can only hope, a catalyst for further civic work, within and beyond the library and the museum.

[1] Mattern, Shannon. “Local Codes: Forms of Spatial Knowledge”. Public Knowledge. (January 18, 2019). https://publicknowledge.sfmoma.org/local-codes-forms-of-spatial-knowledge/.

[2] Smith, Zadie. “The North West London Blues”. The New York Review of Books. (June 2, 2012). https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2012/06/02/north-west-london-blues/.

[3] Mattern, Shannon. “Public In/Formation”. Places Journal. (November 1, 2016). https://placesjournal.org/article/public-information/?cn-reloaded=1.

[4] San Francisco Public Library. “San Francisco Public Library Annual Report 2017-2018”. SFPL. https://sfpl.org/pdf/about/administration/statistics-reports/Annual-Report2017-18.pdf.

[5] The United States Census Bureau. “California High-Speed Internet Use Varies by Metro Area”. The United States Census Bureau. (April 26, 2018). https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2014/cb14-r36.html.

[6] Graham, et al. On The Edgware Road, Serpentine Gallery, London and Koenig Books, London, 2012

[7] Swanson, Don R. “Undiscovered Public Knowledge.” The Library Quarterly 56, no. 2 (April 1, 1986): 103-18. doi:10.1086/601720.